Boston University Researchers Publish Study Conducted in Burlington's Landlocked Forest

The site, chosen for its biodiversity, was one of six used for a study of the organisms in soil that support soil fertility and tree growth

Below our feet is a thriving environment many of us don't often think about. Organisms in the soil – often so small they can't be identified by a microscope, let alone seen by the naked eye – work around the clock to support the healthy growth of the trees around them. And some groundbreaking work to identify these species and study what they do to support the ecosystem was performed right here in Burlington.

The Landlocked Forest, bordered by conservation land in Lexington and Bedford and by heavily-trafficked roadways in Burlington, was chosen by researchers in Boston University's Bhatnagar Lab of Microbial Ecology for a study whose field work was completed mostly in 2021 and 2022, said lead researcher Corinne Vietorisz.

Vietorisz's work, she said, seeks to answer the question, "Which types of microbes in the Massachusetts soils are most important for the soil processes that maintain fertility?" She and her fellow researchers spent four years studying the fungal and bacterial species living in the soil in six different forests in Massachusetts, and she found the Landlocked Forest unique among suburban forests.

"I had walked around and realized it was a large natural area with a lot of pines," she said, adding that the area had a lot of biodiversity for such a small space. "We care a lot about the diversity of trees, because that impacts the diversity of microbes below ground. So when trees are more diverse, soil microbes tend to be more diverse."

These microbes are associated with decomposing leaf litter on the forest floor, as well as supporting tree growth by transferring phosphorus, nitrogen, and micronutrients from the soil to the trees in exchange for sugar – and they're species-specific, meaning a maple, a pine, and an oak might have completely different sets of associated soil microbes that support in breaking down its dead components and helping its living parts thrive.

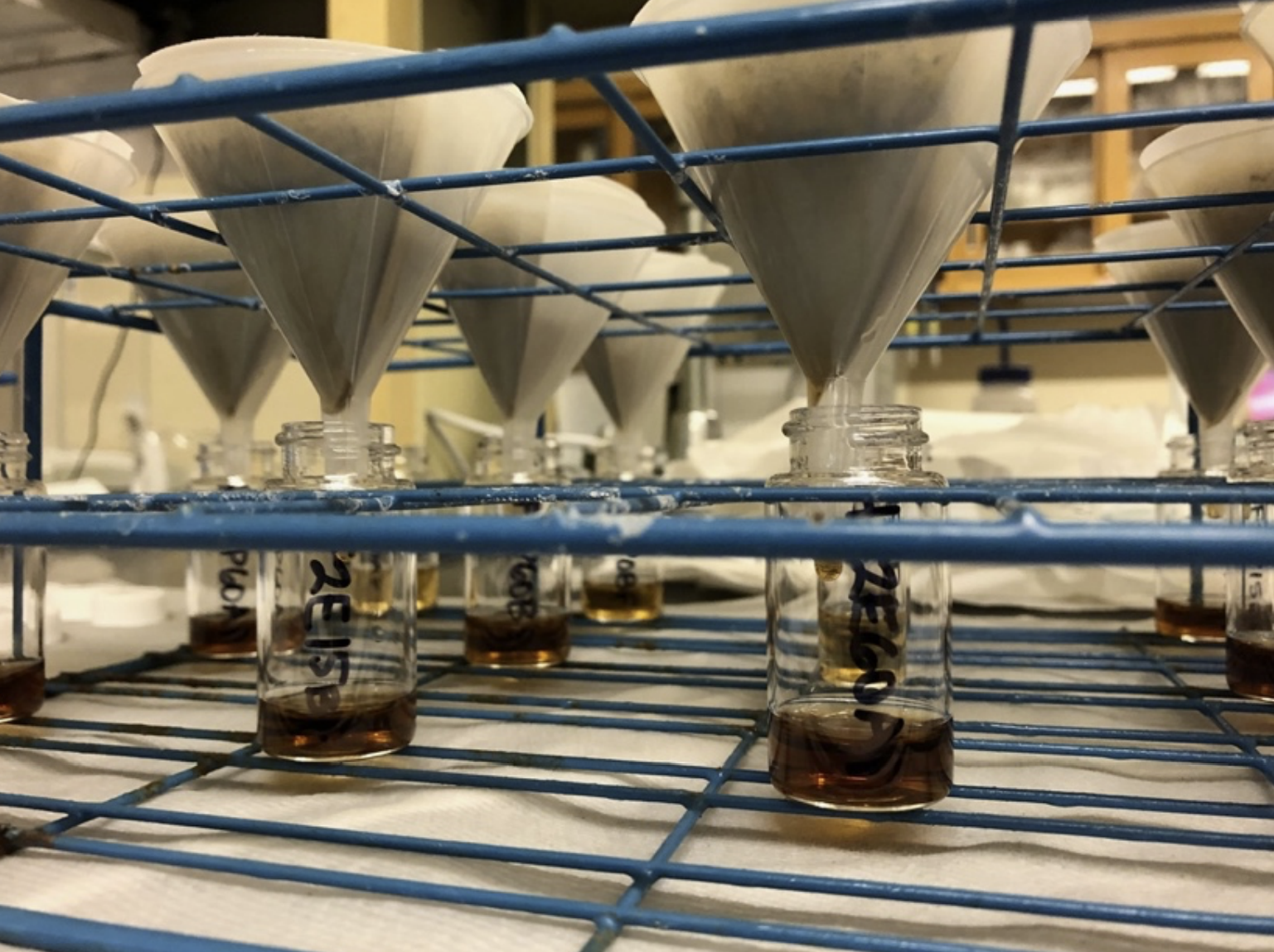

Researchers, assistants, and both undergraduate and high school students worked in the Landlocked Forest in the early 2020s, examining leaf litter, soil, and tree growth in an effort to understand how the ecosystem works together.

Vietorisz describes the work of soil microbial research as trying "connect the unseen with the seen," and, in a paper published in November in the scientific journal Ecosphere, she and her co-authors do just that.

"We did come away with the finding that the root symbiotic fungi, specifically the ectomycorrhizal fungi, were really important for [the process of nutrient transfer from the soil to the trees]," she said, "And then interestingly, we found certain groups of bacteria, we kind of call them N-decomposing bacteria – nitrogen decomposers – they were really important as well."

Knowing what soil microbes are present in different environments and how they work to support the health of forests can help with land management, Vietorisz said, giving us the tools we need to maintain soil fertility even in suburban and urban environments where soil quality isn't always top-notch. They can also help scientists predict how different forests and species will respond to changing environmental conditions.

Much research is being done in the field to identify the organisms living in the soil, said Associate Professor Jenny Bhatnagar, but Corrine's work takes the process one step further to describe the work that the organisms do. This requires analyzing an organism's genes, or DNA (identifying what it is), and looking at its RNA, the molecule associated with how those genes are expressed (identifying what it does).

"Only in the last couple decades have the technologies existed to even study the soil," said Vietorisz, and this has created a boom in the field. "There's so much work going on right now on who's there and what are they doing, and so much of this work is revealing how important they are. Soil microbes, human microbes, any kind of microbe, they're just driving so many processes. Whether it's [soil] fertility, tree growth, carbon flow in the ocean, there's so many different things."

And, if you're one to get nervous about the idea of invisible organisms in the forest, Bhatnagar is here to reassure you there's no cause for concern. "The vast majority of microorganisms out there make the world go round," she said. "They're not there to make you sick."

Read the full paper here, and then visit the Landlocked Forest (Park at the Turning Mill Road lot in Lexington) to see the biodiversity that made it such a great research site.

From top left: 1. Mushrooms of the genus Amanita, a fungus that is symbiotic with tree roots, in a stand of white pine trees in Landlocked Forest. While the bulk of the fungus is belowground attached to tree roots, it sends up a reproductive structure (a mushroom) to the forest floor. 2. Lindsey Adams, a coauthor on the study, prepares materials for collecting soil samples. 3. Fungal hyphae (in white) decompose a rotting log on the forest floor in Massachusetts. 4. The researchers installed many baskets in Landlocked Forest to collect falling leaves and measure their impact on soil microbes and nutrient cycling. Photos by Corinne Vietorisz.